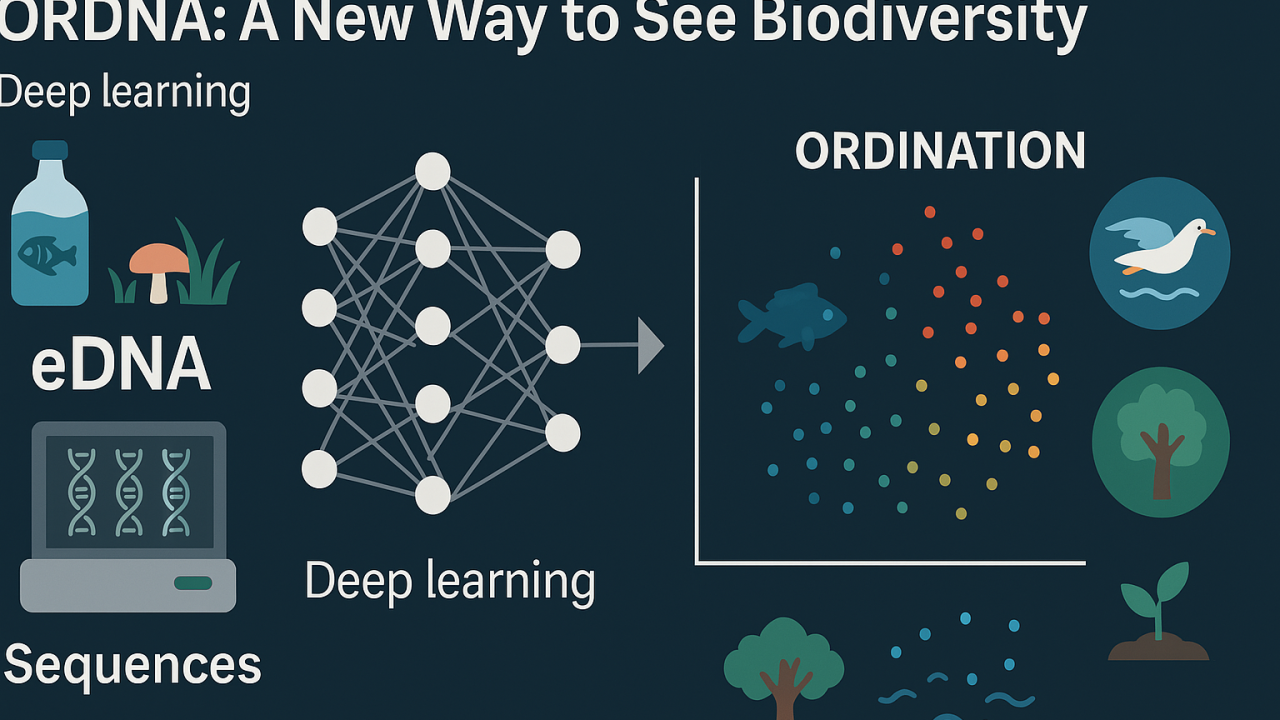

Biodiversity monitoring is a cornerstone of ecological research, guiding conservation initiatives and environmental policy. Traditionally, this research has grappled with complex challenges, especially in accurately measuring and interpreting the intricate relationships within ecosystems. However, recent advancements in technology, particularly in environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding and deep learning, have introduced transformative methods for studying biodiversity. A recent publication introduces an innovation called ORDNA (ORDination via Deep Neural Algorithm), a pioneering tool leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) to redefine how we analyse and interpret eDNA metabarcoding data.

The Importance of eDNA Metabarcoding

eDNA metabarcoding has emerged as a non-invasive, cost-effective method to assess biodiversity. It involves sequencing DNA fragments that organisms shed into their environments, such as water, soil, or air samples. Raw DNA sequence data is inherently complex, high-dimensional, and often noisy due to errors in amplification or sequencing. These issues necessitate extensive bioinformatic preprocessing, such as denoising, clustering into molecular operational taxonomic units (MOTUs), and taxonomic assignments using reference databases. While essential, these preprocessing steps can introduce biases, reduce accuracy, and ultimately obscure valuable ecological patterns.

Enter ORDNA: A Direct Approach

ORDNA takes a different route. Instead of refining or trimming the data before analysis, it processes raw eDNA sequences as they are. The key is self-supervised learning (SSL), a cutting-edge subset of machine learning designed to extract meaningful information from unlabelled data. The central concept within ORDNA is the “triplet loss” function. In simple terms, triplet loss places samples with similar genetic reads closer together in a new, low-dimensional space and pushes apart those that differ.

By performing this analysis directly on raw data, ORDNA preserves delicate genetic signals often lost in standard workflows. The result is an ordination (or “map”) of samples that better reflects how species clusters align with real-world ecosystems. This efficient, more faithful representation of biodiversity is a significant step forward, as it can reveal subtle distinctions between different sites or times that older methods might miss.

Validating ORDNA: A Global Dataset Perspective

To test its value, the research team used ORDNA on four distinct datasets from different ecosystems. Each dataset posed a unique challenge, and ORDNA consistently matched or outperformed standard ordination tools like Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA).

Freshwater Samples from French Guiana: The first dataset looked at fish eDNA in rivers using a 12S rRNA gene fragment. By focusing on raw sequence data, ORDNA teased out a smooth biodiversity gradient from river sources to downstream regions. Traditional approaches, by contrast, sometimes produced fragmented patterns, possibly reflecting the loss of subtle details in standard data processing.

Marine Samples from Brittany, France: Over three years (2020–2022), researchers collected marine eDNA to check for shifts in species composition. After ORDNA was trained on the 2020 data, it was able to project the following years’ samples onto the same “map”, revealing changes in ecosystem structure over time. This ability to handle time-series data without re-training a model from scratch can help scientists track evolving environmental threats.

Forest Soils Across Switzerland: Forest ecosystems contain intricate webs of life, from fungi and insects to microbes. Soil eDNA was taken from both managed forests and more untouched reserves. ORDNA reliably grouped samples according to how they were used and maintained. Most managed forests were distinguishable from forest reserves, showcasing how ORDNA can highlight the impacts of human activity.

Mercury-Polluted Soils in Visp, Switzerland: This last dataset examined soils contaminated with mercury. ORDNA revealed distinct spatial patterns that correlated with pollution levels. In fact, it better separated contaminated sites from cleaner ones than PCoA, indicating it might be especially sensitive to environmental gradients like pollution levels.

Across all four examples, ORDNA either matched or surpassed standard ordination methods in illustrating real ecological transitions. Its non-linear “maps” captured subtle signals that might otherwise have gone unnoticed.

What Makes ORDNA Different?

Several features set ORDNA apart from established techniques:

Avoiding Data Loss: By skipping regular steps like denoising or alignment with reference databases, ORDNA minimises the loss of rare or delicate signals. Traditional techniques risk discarding potentially useful information in an effort to remove noise.

Non-Linear Embeddings: Methods like PCoA often rely on linear assumptions that are not well-suited to complex genetic data. ORDNA’s deep learning architecture reveals non-linear links, painting a more accurate picture of ecological patterns.

Adaptability to Different Habitats: ORDNA has already shown promise in various settings: tropical rivers, ocean samples, forest soils, and polluted sites. This flexibility means it can be used in multiple conservation and research efforts without needing major changes.

Time-Series Analysis: Once ORDNA is trained on a set of data, fresh samples can be quickly placed on the existing “map”. This feature is invaluable when tracking seasonal changes or monitoring areas over several years, as researchers do not have to start from scratch every time.

Fast Projections: Though training a deep learning model can require powerful computers or GPUs, the finished model runs quickly on new data. This allows researchers to analyse eDNA in near real-time once the system is set up.

Where ORDNA Could Improve

Like all new tools, ORDNA has its limits. One drawback is the intense computational cost of training. Another challenge is the occasional appearance of “circular” patterns in the embeddings, which may stem from how the model generalises the data. Researchers are looking to refine ORDNA’s architecture and learn more about its behaviour under different conditions.

There is also a wider question of explainability in deep learning. Many neural network approaches are criticised for being “black boxes,” making it hard for researchers to see why ORDNA arranges samples the way it does. Building in features that clarify which parts of the genetic data have the most influence could boost trust in the tool among ecologists and policymakers.

Potential Directions for Future Research

As ORDNA evolves, several areas stand out for further development:

Bigger, More Varied Datasets: Using larger and more varied collections of eDNA—covering more taxa, primer sets, and sequencing platforms—could strengthen ORDNA’s overall performance. More diverse training data often leads to more robust machine learning models.

Integration with Other Analysis Tools: The embeddings generated by ORDNA might serve as inputs for other methods. For example, ecologists could use these embeddings in species distribution models or network analyses to explore relationships between species in even greater detail.

Deployment for Non-Experts: Making ORDNA easier to use for people outside data science—such as conservation workers, policymakers, and land managers—would broaden its reach. User-friendly interfaces and automatic pipelines could allow real-time decision-making in the field.

Clearer Interpretations: As interest in “explainable AI” grows, future versions of ORDNA might highlight which DNA sequences drive patterns. This clarity could help ecologists identify the key genetic markers that signal ecological changes.

Real-World Benefits for Conservation and Management

The main appeal of ORDNA is its direct insight into raw eDNA data. By capturing ecological nuances that might be flattened or removed in standard workflows, it paves the way for more targeted conservation measures. For instance, a polluted site may harbour resilient but less apparent species that traditional pipelines overlook. ORDNA’s sensitivity could reveal these survivors, guiding strategies for restoring the habitat.

In freshwater or marine environments, where conditions can change quickly, ORDNA can spot small shifts in biodiversity from one year to the next. These shifts might be warning signs of overfishing, climate change, or invasive species. With near real-time updates, agencies could act faster to curb harmful activities or protect key habitats. Over the long term, governments and NGOs might use ORDNA as part of larger programmes that take global snapshots of biodiversity, pinpointing risk zones before it is too late.

In forest ecosystems, soil eDNA often holds clues to management practices and conservation outcomes. By revealing how logging or urban development impacts local species, ORDNA could help policymakers strike a better balance between economic interests and ecological integrity. Similarly, in heavily industrialised locations, ORDNA can measure how well remediation efforts are working by comparing fresh data with historical baselines.

Towards a Deeper Understanding of Life on Earth

ORDNA signals a leap forward in our ability to interpret eDNA data, showing just how powerful AI can be when applied to ecology. By working with raw sequences, it captures the full complexity of ecosystems, helping us see how species communities interact and respond to pressures like pollution, habitat loss, or climate change. Though it is still young and subject to improvement, ORDNA exemplifies how technology can drive ecological research in new, more revealing directions.

One of the biggest challenges facing researchers, conservation groups, and governments is how to keep pace with the rapid changes battering our planet. Tools like ORDNA could be vital in mapping and monitoring these shifts at speed. As it matures, we may see a time when conservationists in the field collect soil or water samples, feed them into a user-friendly ORDNA system, and get immediate, detailed biodiversity readings. That immediacy could inspire faster, evidence-based action to protect threatened habitats and species.

Leave a Reply